|

Switch to Russian |

First and foremost, let's delve deeply into why this shouldn't be done. Imagine the vocabulary of a language as a set of words, and attempt to match elements between two such sets. Will the correspondence be unequivocally mutual?

On two riverbanks, words from two languages reside. Spanning the river is a bridge, across which we guide words hand in hand, seeking to find their counterpart on the opposite shore.

Will every word find its match, and will these matches be unique? Let's use the same example of the word "table."

Even such a simple word is reluctant to be translated unequivocally. Countless words in any language have no direct equivalents in others. "She seemed a true image of Du comme il faut (Shishkov, forgive me: I don't know how to translate)," wrote A. Pushkin about Tatyana Larina.

Let's look at the word "fortune." Every second protagonist in an English folk tale starts by leaving home "to seek his fortune." In literary translation, it would mean "seeking his happiness," but should we assign the concept of "happiness" to this word? Soon children encounter this word in another context: "He caught his death of cold...He left her a comfortable fortune and a daughter." Imagine, upon dying, a husband leaves his heartbroken widow with a daughter and ... happiness. Now, let's contrast the words "happiness" and "fortune." Yes, he lived his life happily, but the only thing he couldn't do was "to make his fortune." In the song "money-money," we find the word in this context: "to win a fortune." In all these examples, it's clear that "fortune" directly relates to money (and luck in the last one).

*) examples are taken from S. Maugham's stories "Louise" and "Home."

So, going back to our fairy tale, should we translate it as "he went to seek his money"? Let the word "fortune" remain as it is, just like all English words, like cornflower and daisy. When I see a makeshift vocabulary list in a notebook divided into three columns (English, transcription, Russian), I immediately associate it with a vocabulary graveyard because a word with a forced definitive translation is a word killed, dead. It cannot continue to live freely, breathe, and evolve in different contexts.

"Kisses don't bear a name,

Kisses aren't inscriptions on tombs..."

...Such inscriptions on tombs are for me words in a mournful black frame, above which is printed the verdict: "Learn new words." And even above them, the lesson number - like birth and death dates that coincide, the words died... attempting to be born.

"... Love doesn't require pledges,

With it, one knows joy and hardship,

'You're mine' - only hands can say,

Tearing off the black veil..."

This beautiful poem "Shagane, you are mine, Shagane" by S. Yesenin can be considered an anthem to the communicative teaching method. In conclusion, we deduce:

(Note: This is a continuation and translation of the given poetic context. Please provide the content or the direction you want the conclusion to take, and I'll be happy to assist!)

Indeed, when you translate phrases, you quickly realize that direct translations often don't work, as each language has its own unique structure, idiomatic expressions, and cultural nuances.

Translating individual words can sometimes be misleading. Languages aren't just a collection of words; they represent an entire cultural and historical context, a specific way of thinking. The structure and syntax of a sentence in one language might not have a direct counterpart in another, and this reflects the different ways people perceive and interact with the world.

The example given about the translation of "What is your name?" is a great demonstration. In English, the phrase is quite literal, focusing on the noun "name." Meanwhile, the Russian equivalent, "Как тебя зовут?" (How are you called?), approaches the question from a different angle, emphasizing the action of calling.

Another striking example is "Сколько тебе лет?" (literally, "How many years to you?"), which in English becomes "How old are you?" Here, again, the focus is shifted - the Russian version emphasizes years, while the English one concentrates on the state of being old.

This isn't to say that one language is richer or more expressive than another. They're just different. Each language encapsulates a unique worldview and understanding. Translating between them isn't merely about swapping words; it's about conveying concepts, emotions, and cultural nuances.

When one learns a new language, they're not just learning words. They're gaining insight into a different culture, a different way of thinking, and a different way of seeing the world. This is the beauty and challenge of language learning. Thus, while translations can help bridge understanding between languages, to truly "get" another language, one must immerse themselves in its culture, history, and nuances.

In conclusion, when crossing that bridge between languages, it might be more beneficial to experience the journey fully, rather than merely transferring words from one side to the other. Language should be translated into concepts and emotions, not just words.

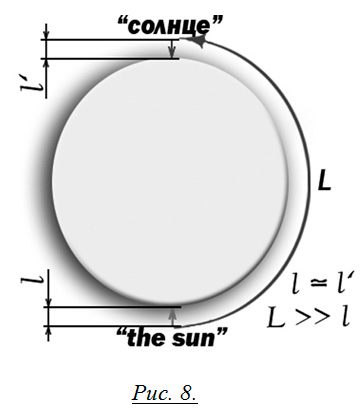

We have before us a concept (a certain fiery disk in the sky) which people in different parts of the world, without knowing about each other, identify as "солнце", "the sun", "le soleil", etc. (Fig. 8).

Let's assume that our native language is Russian. On the illustration, diametrically opposite to it, is shown the foreign language that is being learned first. As is known, subsequent languages are learned much faster, hence they can be placed closer. Thus, we have two ways to define the meaning of the word "the sun", i.e., to connect the word with the concept. Our thought can travel a massive semi-circle from "the sun" to "солнце" (arc L), and then through a short "tunnel" (segment) to the concept (i.e., to the disk). It takes longer, but it's reliable since in our native language, this "tunnel" has already been carved out.

(*We use the notion of a tunnel as a passage carved through rock. Perhaps in this context, the phrase "building a bridge" might be clearer, but we've already used it when transitioning from one language to another.)

Another way: we try to carve a new tunnel from the word "the sun" directly to the concept (segment). This path is a thousand times simpler and shorter, but it's unconventional and requires effort. So, teaching a child to think in a language means building these very "tunnels" from the very first lesson, not allowing the thought to take a detour.

If a child has already gained experience in studying a language through "traditional" methods, the task becomes much more complicated. The teacher has to constantly redirect the child's thinking and block these previously learned channels. Sometimes at the beginning of our lesson, when we do artistic dictations, children echo me, murmuring under their breath, mirroring my speech, transferring words to the tip of their pencil. Everything happens so quickly; they simply don't have time to translate. When I started teaching a group of seven-year-olds with preschool language learning experience, I faced this problem: a child, perfectly understanding me, doesn't trust themselves. Before touching the pencil to the paper, they double-check each step in Russian: "Triangle, right? Green, right?". Yet, in reality, if we don't send the child on a misleading detour, the tunnel path is much easier and more natural.

Example: A five-year-old girl who lived in Israel for two years chats in Hebrew just as freely as in Russian. Relatives from Russia come to visit and observe a scene: on the beach, an entertainer plays with children, and every time he says the word "shalosh," the kids scream and fall into the sand. The Russians ask the girl:

- What does "shalosh" mean?

She shrugs.

- But you fall with everyone, so you understand what it means, right?

- I do!

- So, what is it?

Almost driven to tears, she showed three fingers and shouted, "Shalosh! Shalosh!"

It's not that she forgot the Russian word for "three" (at that moment, her Russian was much better than her Hebrew). It was just hard for her to "translate."

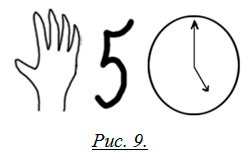

When I test a child for "linguistic purity," for the absence of unnecessary baggage, I ask the parents if your child already knows that "five" is "пять"? If yes, that's bad, especially since "five" is not "пять."

- So, what is it?

Anything you like (see the figure).

But not "пять," not "fünf," not "cinq"... If someone handed you an apple saying "Take an apple!", didn't you understand what was given to you? If you don't trust your eyes, touch it with your hands, bite it with your teeth, but don't label it with the word "яблоко" (apple) - it won't make it any sweeter because of that!

Let's consider an example of how quickly a child can learn to think in another language.

Example:

It's the second lesson with five-year-old children. We're playing hide and seek. We eagerly search the room for a teddy bear I've hidden. This time, I didn't hide it under the table or in a box, but... behind my back (tucked into my belt). It was a funny trick - just to lighten the mood and amuse the children. Suddenly, a spark of realization flashed in a little girl's eyes (the teacher was moving in a somewhat odd way), and she exclaimed, "Turn around, Mrs. Goodwill!". This was completely unexpected and was not part of the lesson's objective! Just before this, during the first and at the beginning of the second lesson, we had sung and played songs with this phrase ("Turn yourself around," "One, two, three – turn around") and turned around while doing so. The child, in a slightly stressful situation (having caught out the teacher, guessed right, and found the bear!), retrieved the appropriate phrase from the songs to "turn" the teacher around.

Thus, we introduce core vocabulary directly through gestures and objects, using them as foundation bricks, and we build subsequent vocabulary like a building on this foundation, defining new concepts using previous ones, that is, creating our own explanatory dictionary.

Example:

The word "palace" is introduced through "A big beautiful house for the King" ("big" is expressed through a gesture, "beautiful" through facial expression and the antonym to "ugly", using intonation, "house" through pictures, "King" as the father of a prince).

- So how do we ensure the child understands the word?

There are many ways to check this understanding, other than translating into Russian (or from Russian to English, as is customary in vocabulary dictations). Initially for toddlers, this can be done through drawing, facial expressions, and gestures. In other words, we essentially retrace the same chain through which these words were presented. Later, at a more advanced stage, understanding can be gauged through selecting synonyms or antonyms from a list, pairing words with related meanings, or inserting a word into the correct context. And finally, by providing a definition of the word in the same language. Essentially, this is how vocabulary is processed in any well-composed reading book. And when we learn to think in another language, our efforts are rewarded by a deeper understanding of different ways of thinking.

The fact that in figure 8, from the word "the sun", we travel through a tunnel and emerge on a disk on the other side is very symbolic. Any other language indeed makes us look at a phenomenon or object from a different perspective. By shedding light on the same object from different angles (studying different languages), we delve deeper into the essence of things.

Examples of such different views on the same things are countless. Conducting such studies, one could write not just one book, which would be read with great interest not only by linguists. I recently heard on M. Zadornov's program: "Only in Russian, in the word for 'rich' ('богатый') does the root 'god' ('бог') exist. And the word 'hero' ('богатырь') came from the words 'god' and 'accumulate' ('тырить') – where the latter word doesn't mean 'to steal,' but 'to gather'." When translating this word into any language, it naturally loses both roots, and thus loses its deep original meaning.

To this day, I continue to be amazed and admire the discoveries that "illuminating" objects from the side of different languages gives me. I want to provide one example that struck me deeply when I first started learning English...

The concept of "my husband's mother" or "my wife's mother" is precise and identical for all people. But they call them quite differently. Russians use the terms 'mother-in-law' and 'mother of the spouse.' The French (identically for both) say "belle mere" (beautiful mother), perhaps with a touch of French humor. And the English... for both... "mother-in-law"! That is, we choose our partner out of love, but his (her) mother we are obliged to respect as our own by law! This is how strictly the English name all relatives-in-law with the prefix in-law – sister-in-law, brother-in-law... it's like a refreshing rain on the heated brains of our compatriots with all their endless toxic jokes about evil mothers-in-law, pitiful songs about wicked mothers-in-law, and sayings about preferring four brothers-in-law to one evil sister-in-law... Probably the English would simply not understand Y. Trifonov's words in the story "Exchange" that "the union of two people is the collision of two galaxies."

In our language, 'mother of the spouse' translates to "holy blood." The word for 'mother-in-law' has an unknown origin, but the spicy salad called "mother-in-law's tongue" is well known in the culinary world.

So, as the mother of two daughters and twice a mother-in-law, I have the right to be offended by my native language. What "holiness" was missing in my blood to reach my daughter's spouse? So mothers! If you want to get the title of "beautiful mother" - marry your daughters to Frenchmen! – it's a joke, of course. A Russian son-in-law is still closer. And as for the term mother-in-law, let's draw from the Russian treasury of suffixes – and transform into a softer version of the term – then it's not so offensive.